The process of selecting an appropriate plastic shredder constitutes a critical technical decision within recycling and manufacturing operations. This selection directly influences operational efficiency, final product quality, and long-term economic viability. The core of a scientific selection methodology rests upon a comprehensive analysis of the target material's fundamental mechanical properties, specifically its hardness and toughness. These two attributes dictate the mechanical stress and energy required to fracture the plastic. A mismatch between machine capability and material behavior leads to suboptimal performance, including excessive wear, energy waste, and inconsistent output. This guide provides a systematic framework for matching the distinct operational principles of single-shaft, dual-shaft, and four-shaft shredders to the hardness-toughness profile of plastic feedstocks, enabling informed capital investment and process optimization.

Understanding the Core Selection Criteria: The Science of Plastic Hardness and Toughness

The terms hardness and toughness possess specific definitions within materials science, extending beyond everyday language. Hardness quantifies a material's resistance to surface indentation or permanent deformation. It is measured using standardized scales such as Rockwell or Shore Durometer. A higher hardness value indicates a greater resistance to being scratched or dented. In practical terms, a hard plastic like polystyrene (PS) will strongly resist a cutting blade's initial penetration. Toughness, in contrast, defines a material's ability to absorb energy and plastically deform without fracturing. It is often characterized by metrics like impact strength (Izod or Charpy tests) and elongation at break. A highly tough material, such as low-density polyethylene (LDPE) film, will stretch and deform significantly before finally tearing.

The interaction between hardness and toughness determines the fundamental challenge of size reduction. High-hardness, low-toughness materials, typical of many brittle engineering plastics, require the application of high force to initiate a crack, but once started, fracture propagates easily. High-toughness, lower-hardness materials present a different challenge. They yield under force, absorbing substantial mechanical energy through deformation rather than clean fracture, often leading to wrapping around equipment components. The selection of a shredder must directly address this primary mechanical behavior to be effective and efficient.

Testing Methods and Practical Industrial Assessment

Formal material characterization relies on laboratory tests following ASTM or ISO standards, providing precise numerical data for hardness and impact strength. In an industrial recycling context, such detailed data is often unavailable for mixed or post-consumer waste streams. Practical, rapid assessment techniques are therefore employed. Operators may perform simple manual tests: attempting to cut or scratch the material with a tool, bending it to observe if it snaps cleanly or deforms, or noting its behavior under a hammer strike. While qualitative, these methods, combined with experience in identifying common plastics like PET bottles or HDPE containers, allow for a sufficiently accurate field classification to guide initial equipment consideration.

The Compound Effect of Material Form and Geometry

The intrinsic hardness and toughness of a polymer resin are profoundly modified by its physical form in the waste stream. A given material, such as polypropylene (PP), can manifest as a rigid, thick-walled automotive bumper or as a flexible, woven bulk bag. The thin, extensive geometry of a film presents a vastly different challenge to a shredder than a dense, thick block of the same chemistry. The film form exacerbates toughness-related issues like wrapping and requires machinery with positive feeding and grabbing actions. The dense block emphasizes the need for high cutting force. Therefore, effective selection must consider the combined effect of material properties and physical morphology on the shredding process.

Contaminants Altering Effective Material Properties

Post-consumer or industrial plastic waste is rarely pure. The presence of fillers, reinforcements, and other contaminants significantly alters the effective hardness and abrasiveness of the feedstock. Compounds containing glass fibers, mineral fillers like calcium carbonate, or other plastics create a composite material. These additives can increase apparent hardness and, critically, the abrasive wear imposed on shredder cutting components. A plastic that might otherwise be considered moderate in hardness can become highly wear-intensive. This necessitates the selection of machines equipped with specially hardened or wear-resistant knives and may influence the choice of a shear-based versus a tear-based reduction mechanism to manage abrasion.

The Dynamic Influence of Temperature on Behavior

The mechanical properties of plastics are highly temperature-dependent, a factor with significant operational implications. Many tough plastics become more brittle at lower temperatures, a phenomenon exploited in cryogenic grinding. Conversely, ambient heat can soften plastics, making them more prone to smearing rather than clean fracturing. Some materials, like certain nylons, are also hygroscopic, meaning their toughness is affected by moisture content. Understanding these dynamics allows for process optimization. In some cases, preconditioning feed material—such as chilling films to embrittle them—can transform a difficult shredding task into a manageable one, enabling the use of a different, potentially more efficient machine type for the application.

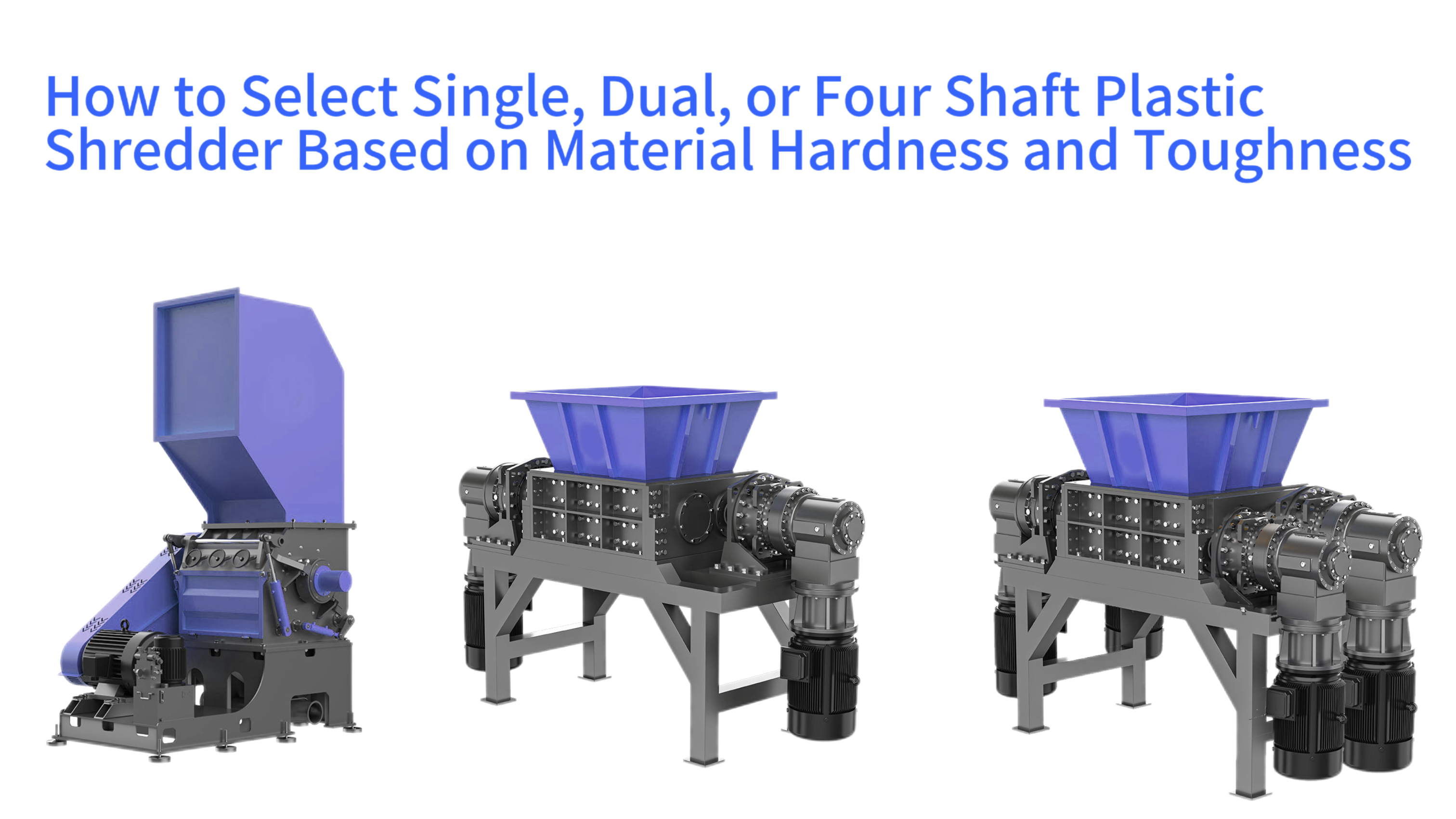

Single-Shaft Shredder: Precision Shear for Medium-Toughness, Medium-High Hardness Materials

The single-shaft shredder operates on a principle of controlled, sequential shear. Its core design centers on a robust, horizontally mounted rotor driven by a high-torque electric or hydraulic motor. This rotor is fitted with several cutting hooks or knives arranged in a helical pattern. A stationary bed knife, or counter-knife, is fixed within the cutting chamber opposite the rotor. The critical action is provided by a hydraulic pusher ram which compactly feeds material against the rotating rotor. The material is captured and drawn between the passing rotor knives and the fixed bed knife, where it is subjected to a precise scissor-like shearing action.

This mechanism excels in processing materials that are prone to clean fracture under shear stress. Its performance boundary encompasses medium to high hardness plastics with low to medium toughness. Typical applications include purgings, thick-walled containers, pipes, profiles, and injection molding sprues. The use of a sizing screen at the discharge ensures controlled output particle dimensions, resulting in uniform chips with minimal fines. The single-shaft shredder is distinguished by its ability to produce a consistent, defined granulate suitable for direct extrusion or high-value recycling, where particle shape and size distribution are important for downstream processing efficiency and final product quality.

Configuration for High-Hardness, Brittle Plastics

When processing brittle polymers such as polystyrene (PS) or acrylonitrile-styrene (AS), the configuration of a single-shaft shredder can be optimized. The primary goal is to achieve clean fracture while minimizing energy consumption and the generation of excessive dust. This is accomplished by employing high-strength alloy steel knives with a sharp cutting geometry, maintaining a very small and precise clearance between the rotor and bed knives, and selecting a screen with a high percentage of open area. The high open-area screen allows properly sized particles to exit quickly, preventing over-processing and attrition within the chamber, which would lead to unwanted fine powder and increased wear on the machine components.

Handling Medium-Toughness Bundled Materials

Certain materials like rolled film or collapsed woven bags possess moderate toughness and a tendency to entangle. To process these effectively in a single-shaft system, specific anti-wrapping design features are essential. The helical arrangement of the rotor knives creates a self-feeding, pulling action that helps draw material into the shear zone. This is augmented by the forced feed of the hydraulic ram. Some systems may incorporate a pre-cutting or perforating stage at the hopper to reduce the effective size and integrity of bundled feeds before they engage the main rotor. This combination of features mitigates the risk of material winding around the shaft, which can cause jams and require operational shutdowns for clearing.

Throughput and Energy Consumption Profile

The specific energy consumption of a single-shaft shredder, measured as energy per unit of processed material, tends to be higher than that of a coarse primary shredder. This is a direct result of its precise, screen-controlled cutting action which performs more work to achieve a defined particle size. Throughput is governed by multiple factors: the inherent hardness of the plastic, the force and cycle speed of the hydraulic pusher, and the restrictive effect of the screen aperture. Machines designed for thicker, harder materials will feature more powerful drives and heavier-duty construction. This configuration is economically justified for processing higher-value in-house scrap or post-industrial waste where the quality of the output granulate directly translates to monetary value in subsequent production or sales.

Maintenance Overview and Typical Application Scope

Maintenance activities for a single-shaft shredder are relatively centralized on the cutting components. The rotor knives and the stationary bed knife constitute the primary wear parts. Their service life depends on the abrasiveness of the processed material. A significant advantage is the accessibility of these knives for sharpening or replacement, which can often be performed without fully disassembling the rotor assembly. This machine type is predominantly deployed in settings requiring controlled size reduction. This includes plastic manufacturing plants for regrinding startup purgings and reject parts, dedicated recycling lines for specific, cleaner waste streams like PET bottle flakes, or any operation where the consistency and cleanliness of the output are prioritized over maximum raw throughput volume.

Dual-Shaft Shredder: The Tearing Specialist for High-Toughness, Entangling Materials

The dual-shaft shredder employs a fundamentally different comminution principle tailored for materials that defy clean cutting. Its defining feature is two parallel, horizontally mounted shafts that rotate at low speed but deliver very high torque. Each shaft is fitted with a series of intermeshing disc- or hook-shaped cutting rotors. The shafts rotate in a synchronized, inward direction, drawing material into the gap between them. The cutting action is not primarily shear but a combination of grabbing, stretching, ripping, and crushing. The intermeshing rotors create a powerful, self-feeding pull that mechanically engages even slippery, flexible items.

This design establishes an absolute performance advantage for high-toughness, high-volume, and easily entangled plastics. Its operational boundary is defined by materials that would typically wrap around a single shaft or simply deform in a shear press. Prime examples include entire rolls of agricultural film, empty or full bulk bags (FIBCs), entangled fiber materials, elastic automotive interior parts, and pre-cut tire shreds. The machine frequently operates without a sizing screen or with a very large-aperture grate, functioning as a powerful volumetric reducer or pre-shredder that transforms unmanageable items into a coarse, strip-like output for further processing or compaction.

Design for Extreme Flexibility in Films and Woven Materials

Processing materials of extreme flexibility and low hardness, such as polyethylene stretch wrap or plastic bags, demands specific adaptations in a dual-shaft shredder. Standard hook designs may be replaced with deep-grab or claw-like刀具 to ensure positive engagement of the thin, yielding material. Rotational speeds are kept particularly low to maximize torque and the tearing force applied. The friction generated within the densely packed cutting chamber can also raise the temperature of the plastic locally. This incidental heat generation can sometimes soften the film slightly, aiding the tearing process. The primary objective is to reliably ingest and mechanically disrupt the material's continuity, overcoming its inherent tendency to clump and wrap rather than to cut it into precise shapes.

Tolerance for Contaminants and Composite Materials

The rugged, tear-based action and typical absence of a fine screen give dual-shaft shredders a notable tolerance for incidental contaminants. Small metallic objects, such as bottle caps or wires embedded in fabric, may pass through the system without causing catastrophic damage, especially when the machine is equipped with protective shear pins or torque-limiting devices. This capability extends to certain composite materials. Laminates of plastic and fabric, or some plastic-metal assemblies, can often be processed, with the shredding action working to separate the constituent materials to a degree. This makes the dual-shaft shredder a preferred frontline solution for mixed municipal solid waste, construction/demolition waste, and electronic waste streams where material homogeneity is not guaranteed.

Throughput and Energy Consumption Characteristics

When configured for primary size reduction (as opposed to fine grinding), a dual-shaft shredder can exhibit favorable throughput-to-energy ratios. Its low-speed, high-torque operation is mechanically efficient for applying massive ripping forces. The energy consumed is directed towards the gross mechanical failure of large objects rather than the precise, repeated shearing required to create small, uniform particles. Consequently, it can achieve high volumetric throughput rates for bulky, difficult materials. This efficiency profile makes it ideal for the initial size reduction step in a recycling line, where the goal is to quickly reduce feedstock volume, liberate embedded contaminants, and produce a more manageable material stream for downstream sorting, washing, or secondary fine grinding processes.

Maintenance and Dominant Application Areas

Maintenance for a dual-shaft shredder involves a larger number of cutting discs or hooks spread across two shafts. While wear may be more distributed and gradual compared to the concentrated wear on a single-shaft's bed knife, the total inventory of wear parts is greater. Proper synchronization and clearance between the two shafts are critical for performance and must be maintained. This machine type is the undisputed first choice for challenging, high-volume waste streams. Its core applications encompass municipal solid waste (MSW) processing facilities, construction and demolition (C&D) recycling plants, agricultural film collection hubs, and facilities handling large, bulky plastic items or industrial packaging waste, where reliability and the ability to process unpredictable feed material are paramount.

Four-Shaft Shredder: Advanced Solution for Fine Grinding and High-Purity Requirements

The four-shaft shredder represents an integrated, two-stage size reduction system engineered for demanding output specifications. Its architecture essentially combines two independent dual-shaft units in a sequential arrangement within a single housing. The first set of shafts functions as a primary coarse shredder, similar to a standard dual-shaft machine, performing initial tearing and size reduction. The pre-shredded material then falls directly into the nip of the second set of shafts. This secondary stage operates, often with different rotor geometry and sometimes higher relative speed, to further refine the material through a combination of shearing, tearing, and grinding actions.

The unique value proposition of this design is its ability to process challenging materials—including those of high toughness or medium hardness—directly into a very fine, homogeneous granulate in a single pass. The material is subjected to sustained and progressive mechanical stress, ensuring thorough size reduction. A finely perforated screen controls the final particle size, which can reach as low as several millimeters or even smaller. This capability is particularly critical for advanced recycling pathways where high surface area and purity are essential, such as in chemical recycling processes or for producing high-quality washed flakes for bottle-to-bottle recycling, where stringent contaminant levels must be met.

Producing High-Quality Flakes for Bottle-Grade Recycling

In the production of food-grade recycled polyethylene terephthalate (rPET) or high-density polyethylene (rHDPE), flake purity and size consistency are non-negotiable. A four-shaft shredder excels in this role. Its two-stage action thoroughly breaks apart post-consumer bottles, including their caps and labels. The intensive shredding promotes the liberation of contaminants like adhesives, paper, and foreign plastics from the target polymer flakes. The output is a clean, uniformly small flake with a high bulk density. This optimal feedstock significantly eases the subsequent washing, flotation, and rinsing stages in a recycling plant, leading to higher yield, lower water/chemical usage, and a superior final pellet quality that can meet demanding OEM specifications.

Processing Complex Packaging with Labels and Coatings

Modern plastic packaging is often a complex composite, featuring printed labels, adhesive layers, barrier coatings, or multi-layer structures. The four-shaft shredder's powerful, multi-stage action is highly effective at tackling these challenges. The sustained mechanical stress works to delaminate layers, detach labels from their substrate, and break down printed ink layers into minute particles. This mechanical liberation of contaminants is a crucial pre-treatment step. It transforms a composite item into a mixture of plastic fragments and detached contaminants, setting the stage for highly efficient separation in downstream hydrocyclones, hot washes, or other cleaning systems, thereby maximizing the recovery of pure polymer.

Investment, Operational Cost, and Economic Justification

As an advanced technological solution, the four-shaft shredder commands a higher initial capital investment compared to single- or dual-shaft units of similar intake size. Its operational energy consumption is also concentrated, given the power required to drive two sets of high-torque shafts and overcome the resistance of a fine screen. A comprehensive economic analysis must therefore extend beyond simple purchase price. The justification lies in the significantly enhanced value of its output and potential process simplifications. By delivering finely-sized, contaminant-liberated flakes, it can reduce the cost and complexity of later cleaning and sorting stages, increase the throughput and yield of the entire recycling line, and produce a recycled resin capable of commanding a premium market price, leading to a favorable return on investment for large-scale, modern recycling operations.

Maintenance Complexity and Targeted Industry Use

The mechanical complexity of a four-shaft shredder is inherently higher, featuring two sets of synchronized shafts, their associated bearings, drives, and a more intricate cutting chamber. Maintenance procedures require skilled technicians and a systematic approach. However, this complexity is managed through robust engineering, advanced control systems for monitoring torque and temperature, and designed serviceability. This machine is not a general-purpose tool but a targeted solution for specific, high-end applications. Its primary adoption is found in large-scale, automated plastic recycling facilities focused on packaging waste, in specialized operations processing post-industrial engineered plastics, and in research or production settings where precise, fine granulation of polymer materials under controlled conditions is a fundamental process requirement.

Core Operational Characteristics of Single, Dual, and Four-Shaft Shredders

| Characteristic | Single-Shaft Shredder | Dual-Shaft Shredder | Four-Shaft Shredder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Action | Precision scissor-like shear | Grabbing, tearing, crushing | Two-stage: coarse tear + fine shear/grind |

| Energy Profile | High specific energy (per unit output) | Low specific energy (volumetric reduction) | Very high specific energy (fine granulation) |

| Wear Part Focus | Rotor knives + bed knife | Intermeshing discs/hooks (two shafts) | Primary + secondary rotor assemblies |

| Output Quality | Uniform chips (screen-controlled) | Coarse strips (no fine screen) | Fine, homogeneous granulate (≤5mm) |

Comparative Decision Matrix: Visualizing Shredder Applicability on a Hardness-Toughness Map

A practical tool for initial equipment selection is a two-dimensional hardness-toughness matrix. This conceptual map places hardness, representing resistance to indentation and cutting, on the horizontal axis. Toughness, representing energy absorption and elongation, is placed on the vertical axis. Common plastic materials can be plotted within this field based on their typical property ranges. For instance, polystyrene (PS) and acrylic (PMMA) occupy a high-hardness, low-toughness region. Polyethylene films (LDPE, LLDPE) reside in a high-toughness, low-to-medium hardness zone. Engineering plastics like polycarbonate (PC) or nylon (PA) may fall into a medium-hardness, medium-toughness area.

Superimposed upon this material map are the dominant operational zones for each shredder type. The single-shaft shredder's zone of excellence covers a swath from medium to high hardness and low to medium toughness. The dual-shaft shredder dominates the region of high toughness, spanning from low to medium hardness. The four-shaft shredder's zone often overlaps the upper-medium ranges of both properties, representing its ability to handle materials that are both somewhat hard and somewhat tough, requiring progressive reduction to a fine output. This visualization immediately narrows the viable machine options based on the primary mechanical characteristics of the feedstock.

Hardness-Toughness Decision Matrix for Shredder Selection

| Low Hardness | Medium Hardness | High Hardness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Toughness | Dual-Shaft LDPE Film, FIBCs | Four-Shaft Nylon (PA), PP Bumpers | Four-Shaft High-Toughness Engineering Plastics |

| Medium Toughness | Dual-Shaft Elastic Automotive Parts | Single/Four-Shaft HDPE, PC, PP Bumpers | Single-Shaft PET Bottles, HDPE Containers |

| Low Toughness | Single-Shaft Soft Brittle Plastics | Single-Shaft Thick-Walled PVC Pipes | Single-Shaft PS, PMMA (Acrylic) |

Quick-Reference Selection Table for Common Materials

Quick-Reference Selection for Common Plastic Materials

| Plastic Material/Waste Item | Hardness-Toughness Profile | Recommended Shredder | Key Operational Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) Sheets/Foam | High Hardness, Low Toughness | Single-Shaft | Use high-open-area screen to reduce dust |

| LDPE/LLDPE Agricultural Film | Low Hardness, High Toughness | Dual-Shaft | Equip with deep-grab hooks for anti-wrapping |

| PET Bottles (Baled) | Medium-High Hardness, Low-Medium Toughness | Single/Four-Shaft | Four-shaft for food-grade rPET flakes |

| PP Automotive Bumpers | Medium Hardness, Medium-High Toughness | Four-Shaft | Two-stage reduction for filler liberation |

| Mixed E-Waste Plastic Enclosures | Variable Hardness/Toughness | Dual-Shaft (Primary) | Contaminant-tolerant initial breakdown |

A supplementary quick-reference table provides direct recommendations for typical waste items. Dense, brittle PET bottle bales are well-suited to a high-power single-shaft shredder for producing clean flakes. Contaminated, baled PE agricultural film is a classic application for a robust dual-shaft machine as a primary size reducer. Automotive bumpers made from filled PP, which can be both hard and moderately tough, may be effectively processed by either a heavy-duty single-shaft or a four-shaft system, depending on the desired final particle size and cleanliness. Mixed, unknown plastic waste from electronic enclosures typically necessitates the robustness and contaminant tolerance of a dual-shaft shredder for the initial breakdown stage.

Incorporating Scale and Financial Considerations

The theoretical suitability based on material properties must be reconciled with practical business constraints. A small-scale recycler with a limited and consistent stream of industrial PP scrap may find a capable single-shaft shredder to be the most cost-effective solution, offering a good balance of output quality and capital cost. A municipal solid waste processing facility handling hundreds of tons per day of mixed, contaminated plastic will invariably prioritize the high-volume, rugged reliability of a dual-shaft system for its primary line. A large, specialized plant dedicated to producing food-grade rPET from collected bottles may justify the significant investment in a four-shaft shredding line, as the technology's benefits in flake quality and washing efficiency directly translate to higher revenues and market competitiveness, amortizing the cost over large throughput.

Planning for Future Process Flexibility

Equipment selection should incorporate a degree of forward-looking analysis regarding potential changes in the feedstock stream or final product requirements. A business expecting to process an increasingly diverse mix of plastics, or planning to upgrade to produce higher-value regrind, might select a machine with inherent flexibility. This could mean choosing a single-shaft shredder with a wider range of available screen sizes and knife geometries, or opting for a dual-shaft system with a higher power reserve. The goal is to avoid a situation where a change in input material renders the capital equipment obsolete or severely limits business development opportunities, ensuring the investment remains viable across a range of plausible future scenarios.

From Theory to Practice: A Systematic Selection Procedure and Configuration Checklist

The transition from theoretical understanding to a concrete procurement decision requires a structured, step-by-step procedure. The initial and most critical step is a precise analysis of the target material. This involves obtaining representative samples and characterizing their composition, average and worst-case hardness/toughness, level and type of contamination (e.g., sand, metals, other plastics), and physical forms (bulky, film, bundles). Reliable data can come from supplier specifications, industry databases, or in-house testing using the practical methods previously described. An inaccurate assessment at this stage fundamentally compromises all subsequent decisions, potentially leading to significant operational and financial penalties.

Parallel to material analysis is the clear definition of production goals and operational constraints. Quantitative targets must be established for hourly or daily throughput capacity and the required upper size limit of the output material. Financial and physical boundaries include the total available budget for the project, the acceptable range for operational energy costs, the footprint available for equipment installation, and noise or dust emission regulations that must be met. These parameters form the non-negotiable framework within which the technically suitable machine must also fit, ensuring the selected solution is both effective and practical for the specific operational environment.

Systematic Shredder Selection Procedure

Characterize Material

Analyze hardness, toughness, contaminants

Define Goals

Set throughput, output size, budget

Map to Matrix

Identify preliminary shredder type

Test Material

Validate performance at supplier facility

Finalize Selection

Analyze lifecycle costs & confirm choice

Developing a Critical Configuration Parameter Checklist

Following preliminary machine type selection, a detailed technical evaluation of specific models is necessary. A comprehensive checklist should be employed during supplier discussions. Key parameters include the installed motor power and the torque rating of the main shaft(s), which indicate force capability. The rotational speed range determines whether the machine operates for high-speed cutting or low-speed tearing. The material specification, hardness, and geometry (e.g., V-shaped, hook) of the cutting knives are critical for wear life and cutting efficiency. Options for screen sizes and open-area percentages dictate output control. Physical dimensions like feed opening size and overall machine weight determine infrastructure needs. Finally, compliance with relevant machinery safety standards (e.g., CE, ANSI) is mandatory for legal operation.

The Essential Role of Material Testing

No catalog specification can substitute for a live material test. Reputable equipment suppliers typically offer the opportunity to process a customer's sample material in a test facility. This trial is indispensable for final validation. During the test, objective observations and measurements should be recorded: the actual achieved throughput rate under realistic feed conditions, the amperage or power draw of the main drive, the temperature rise of the machine and the output material, the particle size distribution and shape of the discharge, and the generation of noise and dust. Any signs of difficulty in feeding, wrapping, or unusual vibration should be noted. The results of this test provide the most reliable forecast of real-world performance and should form the core evidence for the final investment decision.

Framework for Total Lifecycle Cost Analysis

An informed financial decision extends beyond the initial purchase order total. A total lifecycle cost analysis provides a more accurate picture of long-term economic impact. This framework aggregates several cost categories: the initial capital expenditure for the machine and installation; the projected annual energy consumption based on expected runtime and power draw; the cost and replacement frequency of wear parts like knives and screens; estimated annual maintenance labor and spare parts costs; and any costs associated with waste disposal of by-products like dust collection. Comparing different machine options on this holistic basis may reveal that a higher-priced machine with lower energy use and longer-lasting wear parts offers a lower total cost of ownership over a five- or ten-year period.

Planning for Installation, Training, and Support

The final stage of the selection process involves planning for successful integration and operation. The procurement agreement should explicitly include the scope of supplier support. This encompasses detailed foundation and utility connection drawings for proper installation, on-site commissioning and calibration of the machine by factory technicians, and comprehensive training for operational and maintenance personnel. Clarity on post-sale support is equally important: the terms of the warranty, availability of spare parts, and responsiveness of technical service for troubleshooting. Ensuring these elements are in place before commissioning mitigates the risk of prolonged downtime after installation and secures the expected productivity and return from the equipment investment.